Urinating on Sacred Ground

Only in Australia could a unique and profoundly significant historical site be treated with public indifference and official disdain.

The section of Centennial Park in Sydney reserved for people walking their dogs is, on this sunny Sunday, a picture of pleasant 21st century complaisance. Dozens of people mill about while their pets run, chase balls, lie in the sun and, when the opportunity arises, try to hump each other.

This part of the park is a shallow gully with a wide flat area at the bottom. The bank on one side consists of rehabilitated bushland and everywhere else is dotted with mature oak, fig, pine and gum trees, giving the place a faintly European feel. To complete the scene, planes fly overhead, a van sells coffees and ice-creams, and the people, for a change, talk to each other rather than stare at their phones. On the couple of occasions when someone’s pet wanders over to me looking for a pat or some food, its owner apologises and a short, convivial chat ensues.

The only anomaly in this setting of civic harmony is a weird 8m-high circular sandstone pavilion, plonked almost in the middle of this expanse of grass. It has thick columns around the outside supporting what might be a zinc roof and dome. Around the dome are inscribed the words, “Mammon or millennial Eden”, an obscure reference to a long-forgotten Australian poem. It looks incongruous now, but it marks the place where, on 1 January 1901, the creation of our nation as the federation of six states was formally proclaimed and celebrated.

Inlaid into the lawn around it is a ring of stone beyond which dogs are not allowed, but nobody pays it any attention. You don’t have to wait long to see a dog cock its leg and urinate on one of the columns — a sight gag that cartoonists once routinely used as a sign of comical disregard, which is still sadly apt. When I walk around the pavilion, I notice a couple of small plastic bags filled with dog turd, dumped by a dog’s owner instead of walking to the bin at the edge of the park.

There are iron gates between the columns through which you can see inside but which are perennially locked; entering is forbidden, although muddy paw prints indicate that dogs do so anyway. There is no plaque explaining the pavilion’s significance and nobody looks even mildly curious about its presence.

In the middle of the pavilion is the federation stone, the only remnant of the gala event held here on 1 January 1901, when, in the presence of dignitaries who had sailed from around the world, a choir on the western side of the gully (consisting of 15,000 singers, according to one historian) and masses of spectators, Australia became the world’s newest nation at the dawn of a new and optimistic century. That century turned out to be the bloodiest in history, but this new nation nevertheless emerged from it strong and free, an achievement at least worth acknowledging, if not celebrating.

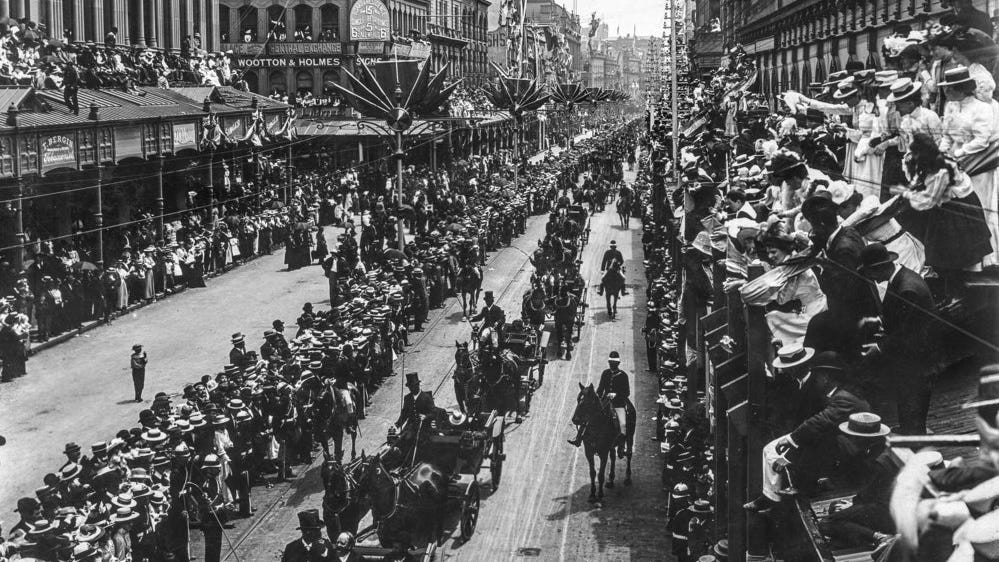

The proclamation of federation was, at the time, the most exciting event to have ever occurred on this continent. The procession of representatives and dignitaries attending the event began a couple of kilometres away at Domain park and followed a route not dissimilar to the one that has since come to more accurately symbolise modern Australia: the Gay Mardi Gras. Tens of thousands of people lined the route, cheering trade unionists, firemen, soldiers (including, among other Commonwealth military, Queen Victoria’s own Royal Horse Guards performing one of the final ceremonies of her reign — she died three weeks later), foreign dignitaries, judges, academics, church leaders, politicians and the man who would that day be sworn in by the governor-general as the first prime minister of the new nation, Edmund Barton.

Like the modern Mardi Gras, the party that night was spectacular. The city was lit up with new-fangled electric lights, the streets were filled with revellers and much alcohol was downed in the official celebration at the Town Hall while an occasional firework flared over the suburbs. Towns and cities across the new nation joined in the new spirit of “One People”, as the sign over the gate to Centennial Park called it. One of the remarkable aspects of this historic celebration is how enthusiastically all levels of government participated. The mayor of Echuca on the Victorian side of the Murray River led a military march to the middle of the bridge, where he met his NSW counterpart from the town of Moama and shook his hand, burying the towns’ acrimony over interstate tariffs, after which the good burghers from both sides joined together in a celebratory feast.

Nobody realised, amid this outpouring of nationwide goodwill, that what they had created would one day become a behemoth at the top of the most over-governed country in democratic history. How could they? As he went about his business as prime minister, Barton remarked that he could keep all the federal government’s affairs in a single briefcase.

The Centennial Parklands Trust, funded by the New South Wales government, is the organisation responsible for maintaining this sacred site. It’s a busy organisation these days, having expanded its remit beyond mere maintenance of the park to include projects and activities that are imbued with the sort of nauseating wokeness that characterises all levels of government these days. It invites people to “join our wellness programs, let your kids discover nature and fun in our holiday programs, or discover the rich cultural heritage of the parklands yourself.” Its educational programs “will bring you a bit closer to the beauty of nature.” But not to history. I emailed the park’s managers asking if it was appropriate to have dogs running around the Federation Pavilion and whether they had any plans to encourage park users to show this sacred site a bit more respect. I received no reply.

This story was originally published in The Spectator Australia in June 2021. Australia’s complacency towards its own history has since then, in my opinion, only worsened.

Weep - for what we once had is not forgotten by time, but neglected by people.

What an interesting piece of history. Today, in Sydney, there are so many people who have come from other countries that our history means nothing to them. A monument that dogs pee on, is just a piece of concrete. My great grandparents and even grandparents would have been there to see Federation and it was such an event. Politicians in those days, did not get paid, they worked hard for the love of this country. I love Australian history, from the first fleet to Federation and beyond. Today, young ones are not taught anything about early history of this country which is so sad. Thank you Fred, for bringing this to print